This story was edited and published by Epic Outdoors in their February 2018 Issue under the title “Elevation”.

A Hard Hunt for an Easy Billy

Guide: Cliff Gray

Hunter: Vince Peisert

“Cliff, there’s a goat right there.”

“Ethan, there is no way in hell…”

I stopped mid-sentence as my binos turned up the undeniable white hide of a goat moving through the low, grass-filled meadow. I’d expect a big muley or bull, but a goat in that country was a surprise! As quick as Ethan had pointed out the billy, he was gone.

I was guiding this hunt for Joe Boucher of Horn Fork Guides in Colorado’s G13. Along with its neighbors G2, G3, and G12, this area was the epicenter of my goat guiding career. However, I was approaching this hunt with some trepidation. Although ranked as one of Colorado’s top goat units, the quantity and quality of billys has been falling here against the Collegiate Peaks. I knew we would be in for an intense and challenging trip. I brought along one of my assistant guides, Ethan Boertje, and the hunter Vince brought along some awesome help of his own, Greg Mashburn. The extra help would end up being a godsend.

There are two types of goat habitat here in Colorado, big baldy scree fields above 12,000 feet and intensely rugged crags in the 10,500 to 13,000 elevation range. G12 and G6 are prototypical examples of the later, while G13 is a perfect archetype of the former. The go-to scouting strategy in the unit is to get to vantage points and glass your eyeballs out for goats maneuvering through the talus. I had stuck to this for a couple days of scouting, turning up a few 2-3 year old billies. I had one more day to scout before the hunt. Ethan and I decided to work some lower elevation chutes. That’s when the “easy billy” showed up.

As we scrambled to get the goat back in our optics before dark, I knew this was where we would spend the first day of Vince’s hunt. The goat was down low in the chute, probably below 9,500 feet, a rare occurrence. They don’t get much easier than that. From where Ethan had originally spotted him, we could have been within rifle range in an hour. That’s almost unheard of with goats. I was certain it was a mature billy. A goat all alone, rambling across the countryside, almost always is. They remind me of old Alaskan men; just trying their best to distance themselves from the trials and tribulations of women and screaming kids.

As we scrambled to get the goat back in our optics before dark, I knew this was where we would spend the first day of Vince’s hunt. The goat was down low in the chute, probably below 9,500 feet, a rare occurrence. They don’t get much easier than that. From where Ethan had originally spotted him, we could have been within rifle range in an hour. That’s almost unheard of with goats. I was certain it was a mature billy. A goat all alone, rambling across the countryside, almost always is. They remind me of old Alaskan men; just trying their best to distance themselves from the trials and tribulations of women and screaming kids.

The only lingering question was, “What in the world was he doing down there?” Had to be water. An unusually warm August and early September had just past. The high elevation drips of lingering snow melt were nonexistent. The billy must have been maneuvering down the slide and catching the only water available. We hit the tents with crossed fingers that he would still be in the same vicinity in the morning.

The next morning we were in position as the first glimmer of light hit the mountain. No billy in the low easy spot. No billy in the aspens above it. No billy in the avalanche chute rising up to real goat country. No billy on the hellish rim. We hiked around the corner to glass the other side of the basin, and there he was. He stood in an open talus field close to 13,000 feet. It was real goat country, and this was going to be a real goat hunt.

We had a couple hours of perfect wind conditions. We would approach the goat via the chute he was in the night before. He would likely feed on the other side for an hour or two and then creep over to our side to bed among the shaded rocks. Our hope was that once the thermal turned uphill, we would be in position to approach him from above. Off we went.

Fresh legs and good spirits always make a 2,000+ foot elevation gain stalk look easier than it really is. An hour and a half in we unanimously decided that just a little bit further and the chute “bowled out”. It would be getting a lot easier. Forty-five minutes later, we realized how comical that thought was. I hadn’t been up in that slide before and realized, with every few hundred yards, this was going to become a mountaineering expedition. Crossings and rocky outcroppings that I had glassed as perfect approaches, one-by-one fell off the list due to a hidden crevasse here or a base of sheer rock there.

Fresh legs and good spirits always make a 2,000+ foot elevation gain stalk look easier than it really is. An hour and a half in we unanimously decided that just a little bit further and the chute “bowled out”. It would be getting a lot easier. Forty-five minutes later, we realized how comical that thought was. I hadn’t been up in that slide before and realized, with every few hundred yards, this was going to become a mountaineering expedition. Crossings and rocky outcroppings that I had glassed as perfect approaches, one-by-one fell off the list due to a hidden crevasse here or a base of sheer rock there.

To add to the challenge, our temperatures were off the charts by mid-morning. The 70-80 degrees had us pulling layers and rationing water. Luckily, we ran into the seep that forced the billy so low the previous afternoon. In my experience, a lone billy can consistently come to water or skip a few days between visits. This water source looked like home for this guy. It even smelt like him.

Feeling very Jim Bridgeresque, I decided to dig out the seep and fill up my water. After all, I am one of the few people that can say they were actually born with giardia. Long story… The thing is, contrary to a bunch of bullshit I have been told, you can still get it again. I have. Hence, I was meticulous by digging way back into the rocks to get a fresh, earth-filtered stream going. We all took a break as I built up a little dam and got a clear pool rising. It was quite the project. I dipped my water bottle in and took a big gulp down. Guess what? It tasted exactly how I imagine billy piss tastes. Smelt like it, too.

The final approach was a scramble through the rim. Our wind had changed, but we were still in good shape as there was no indication we had bumped the goat. Now the thermal, which was buzzing towards the heavens, would be our best friend. Vince and I started by creeping over the edge to the goat’s earlier feeding grounds. He had departed the area but had to be close. We started to maneuver the tight boulders that guided us off the rim to the north.

The thermal brought the distinct smell of mountain goat up from below. We knew he was close now. I dropped through a cracked and there to my left, well under bow range, the billy was bedded against the rim. He was hidden from every angle except mine. I stepped back to grab Vince and get out of the goat’s line-of-sight. My last visual was the goat throwing his front feet up to rise. Now, he knew we were there.

The thermal brought the distinct smell of mountain goat up from below. We knew he was close now. I dropped through a cracked and there to my left, well under bow range, the billy was bedded against the rim. He was hidden from every angle except mine. I stepped back to grab Vince and get out of the goat’s line-of-sight. My last visual was the goat throwing his front feet up to rise. Now, he knew we were there.

Vince and I struggled through the rocks to gain a vantage point for a shot, as the goat departed his bed. He beat us there. The billy stood profile, not 60 yards away, giving us just enough time to admire him as he dropped off the other side.

It’s hard to explain to someone that hasn’t hunted goat terrain, but these moments impose a sense of loss that is hard to imagine. Unlike the analogous situations when deer or elk hunting, you usually can’t see where the animal went or is going. They just disappear into the crags. There is no running up to a high point to see the path of departure. Doing so, just might result in a fatal or maiming fall. Is that the end of the stalk? Did we just burn 3,000 calories and 3 hours for nothing?

All you can do is safely maneuver high and start glassing. Once we got settle in above the massive basin the rim encircled, I started to glass the obvious exit routes. Goats can move incredibly fast through rugged terrain, and we were a good twenty minutes behind him. I still figured we would catch him in a chute across the basin or dropping off a ridge. Nothing. Ten minutes of glassing past and then I heard the words of an angel clothed in Sitka. In a calm voice, Greg says, “I see him bedded right down below us.”

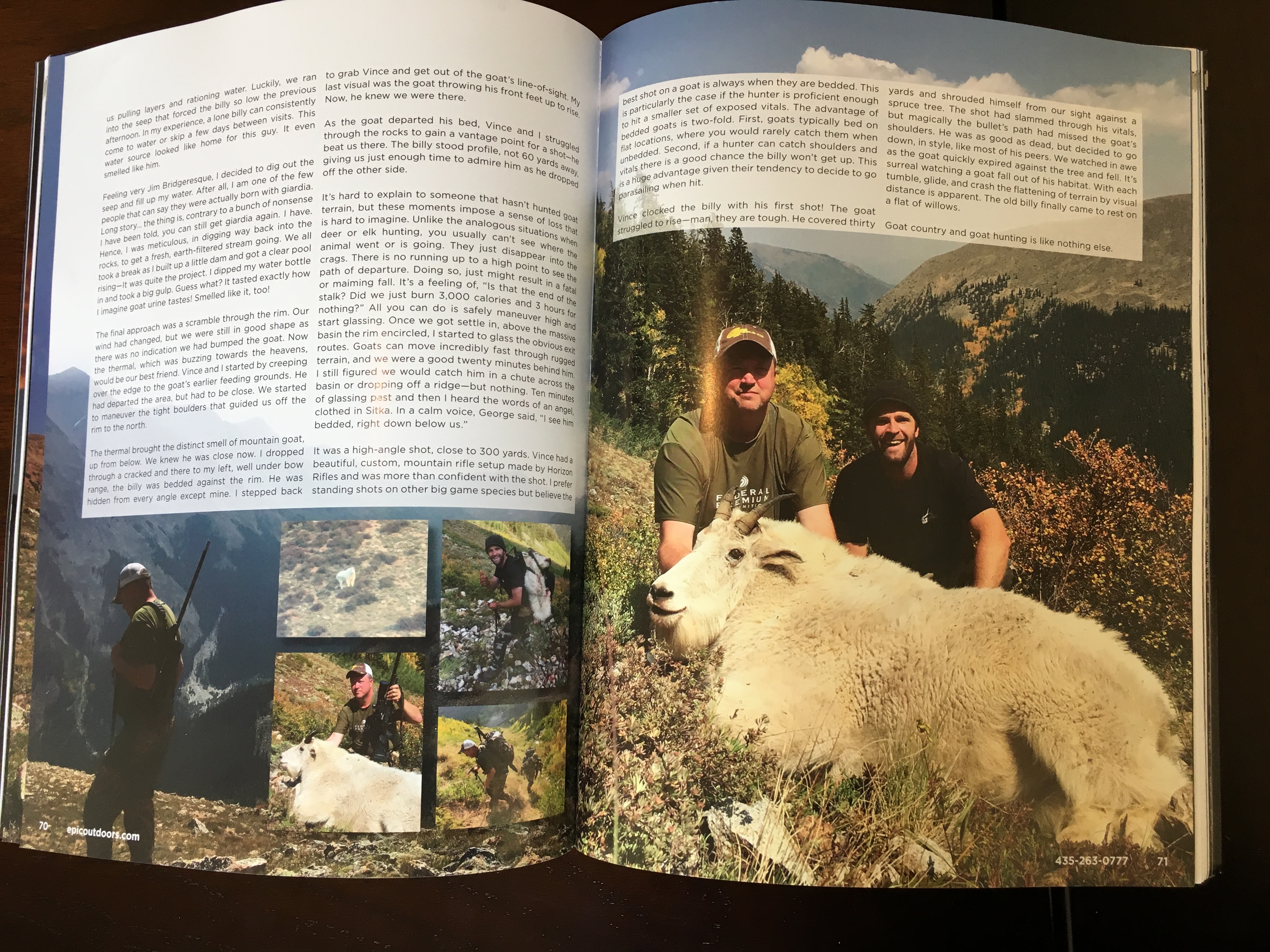

It was a high-angle shot, close to 300 yards. Vince had a beautiful custom mountain rifle setup made by Horizon Rifles and was more than confident with the shot. I prefer standing shots on other big game species but believe the best shot on a goat is always when they are bedded. This is particularly the case if the hunter is proficient enough to hit a smaller set of exposed vitals. The advantage of bedded goats is twofold. First, goats typically bed on flat locations, where you would rarely catch them when unbedded. Second, if a hunter can catch shoulders and vitals there is a good chance the billy won’t get up. This is a huge advantage given their tendency to decide to go parasailing when hit.

Vince clocked the billy with his first shot. The goat struggled to rise. Man, they are tough. He covered thirty yards and shrouded himself from our sight against a spruce tree. The shot had slammed through his vitals, but magically the bullet’s path had missed the goat’s shoulders. He was as good as dead, but decided to go down in style like most of his peers. We watched in awe as the goat quickly expired against the tree and fell. It’s surreal watching a goat fall out of his habitat. With each tumble, glide, and crash the flattening of terrain by visual distance is apparent. The old billy finally came to rest on a flat of willows.

Goat country and goat hunting is like nothing else.

Sign up to get our new posts as they are published!