This article is one of many from our Goat Prep Series

If you don’t want to completely “nerd-out” on mountain goat information, skip down to the hunting strategy section. The first two-thirds of this article is information that I find interesting and some unique observations on goat behavior I have had scouting and hunting them. Of all the animals I spend time hunting, goats are my favorite.

There are several good sources of information on the web regarding mountain goat behavior, but here are two of the most in-depth:

A Beast the Color of Winter: The Mountain Goat Observed

Washington Game Department Study on Goats and Bighorns

Mountain Goat Behavior

Goat Habitat and Habits

Goats are the most uniquely evolved big game animals in North America. From their hide to their toes, they are made for the most rugged country and conditions you can imagine. There are some differences between male/female mountain goats when it comes to habitat, but most goats still spend over 70% of their time on slopes steeper than 40 degrees. To put that in perspective, a set of household stair is typically around 30 degrees (imagine them without the stairs!) and most slopes above 45 degrees are too steep to hold scree over fist size.

The Mountain Goat has “anti-skid” mechanics built into their foot, unlike other big game. The toes can splay apart allowing for better climbing and downhill stopping.

The mountain goat species, when it comes to foraging, is “opportunistic”. Some goats, in some geographies, act a lot like caribou. They eat arboreal lichens, ferns and mosses. In other geographies, they act more like high alpine mule deer; focusing on common mountain browse like service berry, mountain maple, and sedge. Periodically they even act like no other big game species by munching on douglas fir (yes, the tree) and hemlock trees, before using their lower incisors to scrape ground lichens from rock. Goats are survivors.

Here is a quick run-down of forage by area:

Western States and BC Interior – mountain maple, service berry, sedge, ground lichens (off rocks), other sub-alpine browse (BC Interior – add tree lichens)

AK and Coastal BC – tree lichens, ferns, mosses, douglas fir, hemlock trees, sedge and sub-alpine browse when available

Most biologists key in on a “indicator species” when looking at forage conditions for ungulate species. For instance, in Southern Colorado you would look at the condition of Mountain Mahogany to make an assessment of range conditions for mule deer. Unfortunately, goats don’t have a true indicator species of forage. Hence, it is more difficult to manage their populations in relation to the forage present.

When it comes to hydration, I’ve observed mixed goat habits. Some goats will move down to springs on a daily basis. In these situations, the goats will use the cover of a chute’s timber edge to quickly descend to a secluded pool. Once they have gotten a drink they will climb back up, sometimes remaining in the trees until they get back into cliffs to bed.

The second common watering habit I observe is large groups of goats using high alpine lakes. After their morning feeding period, the goats move across talus and scree to lakes that have little cover. Once they are done, the goats will climb above the lake to bed. Sometimes this can be within 200-300 yards, other times they will climb over a rim before bedding. Nursery groups are the most common exhibitors of this type of watering.

The last watering habit I have observed is the most frustrating. This one is common of a solo billy or small bachelor group. They never actually go to water. Instead, they rely on trickles of water that are sourced from glaciated snow pack above timber line. A lot of the time during the hunting season, when it’s warm by goat standards, these billies will bed next to the mini glaciers and you won’t even notice them taking a sip of water periodically.

The other behavior that hunters are likely to observe is “dusting”. In certain locations, particularly at lower elevations near tree line, goats are vigorous about pushing up dirt to cover their hide. This deters bugs from harassing them. You can tell a heavily used bedding area because the beds will look 2-3 times the size of an actual goat. The constant dusting tears up the dry soil and create a find powder. These areas are not random bedding areas, they are spots that goats use over and over.

A nursery group in a dusting area.

I haven’t observed any solid routine around mineral licks. In the geographies I’ve hunted most goats have licks available near their water sources or bedding sites. When they don’t have licks in proximity to their home, they make a random journey every couple days to a nearby lick.

A goat’s daily Fall Schedule:

Morning – concentrated feeding for 1-3 hours

Bedding/Dusting

Midday – slow feeding with intermittent bedding

Go to water if descending to water source

Afternoon – Bedding/dusting

Prolonged feedings into twilight

Goat Predators

Avalanches and rocks are the mountain goat’s biggest predators. It’s true! In an unhunted population, more goats will die from spring avalanches and accidental falls than by predators. In my years of hunting in the Western States, I have never come across a goat carcass that was killed by a predator. In contrast, I’ve come across countless deer and elk that met death via sharp teeth.

In AK, wolves do kill some mountain goats but it has never been considered a major impact on populations. In BC’s coastal areas, lions harvest a fair number of goats as the goats spend time in the timbered and rimrock areas of lion habitat. Grizzlies have been documented “swatting” nannies to death in sub-alpine avalanche chutes in Glacier Park, but again it is pretty rare.

The most intriguing goat predators are eagles. Eagles readily prey on young kids. What’s peculiar is that adult goats appear to be scared shitless of them. I have witnessed, several times, a pronounced reaction from goats when an eagle buzzes the rocks goats inhabit. There is minimal documented proof that eagles kill anything but the youngest goats, so this reaction is likely a remnant of evolution. Mountain goats are close relatives to the Chamois, who is a favorite of eagles to this day.

One interesting phenomenon with goats is they have few predators, yet they one of the best equipped to deal with an attack. A goat’s horns are true weapons. There was a case of lion dogs cornering a billy in BC’s coastal mountains. The goat gored 4 of the 6 dogs to death before the houndsman showed up. There was also a recent case of a human fatally gored in Olympia National Park.

Other than the muskox, the mountain goat has less to worry about on the predator front than any other game animal.

The Goat Rut

Kids are born in early June. This is the case from Northern BC to Colorado. A nanny’s gestation period is around 185 days.

Most billies over 3 years old run in bachelor groups for 10 months of the year, but around mid-November mature billies split up to start trailing nannies. The younger billies in the nursery groups anticipate this change and depart the nannies groups by the end of October. The black glands behind a billy’s horns start to swell during this time.

I find the trailing behavior of goats unique. Unlike deer and elk, a billy isn’t aggressive in courtship. They try to wear down the nannies over a prolonged period, as an alternative. I’ve seen a billy meander 200-300 yards behind a female for several days.

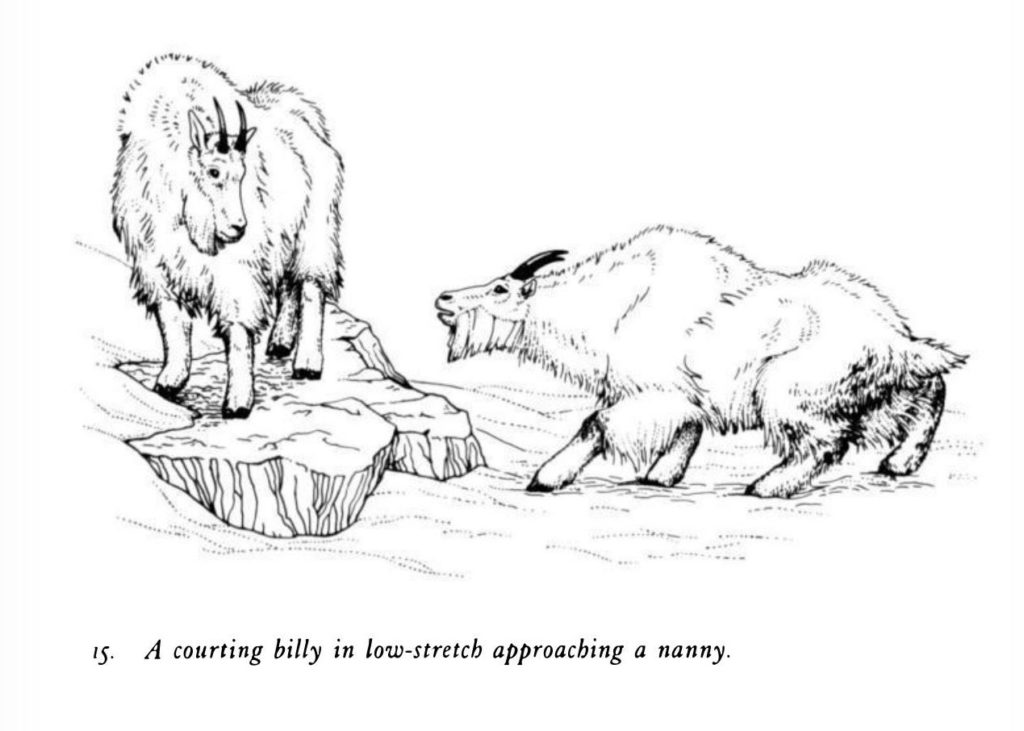

In the first two weeks of December, the billies trail closer and nannies become receptive. By the third week in December the rut is over. Unlike rams, the interaction between billies and between billies and nannies rarely gets violent during the rut. Corresponding to what I have read, my observations have been of goats “hooking” and posturing more than actual rough contact. You see similar behavior, yet toned down, outside of the rut when goats are in close proximity of each other. Biologists theorize that the goat’s lack of violent contact is an evolved behavior related to the danger associated this their sharp horns. For the sake of all goats involved, more show than action is beneficial. Action has a high possibility of resulting in fatal wounds for both parties. Even with this low level of physical contact, several of the goat’s I’ve harvested have had puncture wounds in their shoulders, necks and flanks.

Communication through posturing is prevalent in goats, but my favorite move they make is the “low stretch”. I find it comical, because it appears as if the billy is trying to sneak in for his chance with the lady. The picture below is a great depiction of it from the book, A Beast the Color of Winter.

In my observations, when a billy does this he already knows the nanny will be receptive. He just doesn’t want to blow it by being too confident, I suppose.

Winter and Migratory Behavior

There is conflicting information on goats’ migratory habits in wildlife biology literature. Like their eating habits, these conflicts aren’t a matter of right and wrong. Goats are just uncanny at being opportunistic, so each population acts to optimize it’s own behavior based on its unique environment.

In coastal BC, goats will descend to lower elevations because the snow pack in the thick timber of these areas is too much for even goats to paw through. However, many groups of goats in Colorado will ascend to higher elevation areas that are windswept by exposure.

The key variables goat maintain in the winter is access to high angle terrain and access to food. Coastal goats will descend as far as they can before losing the rugged rimrock. Interior goats, if they aren’t ascending to wind swept areas, will maneuver down valley until they get to the lowest point of steep terrain. It is not uncommon for goats to use natural shelters like caves in both these topographies.

Goats are amazing at dealing with sub-zero temperatures for weeks at a time. They have a few built-in mechanisms for this: 1) Their digestive system actually creates heat. They have a large rumen that holds their feed and creates body heat as they digest. 2) They run hot. Goats have a body temperature 4 degrees above that of humans. 3) They have the most incredible winter jacket on earth.

This billy has just started his winter hide and you can already see the layering of warm layers.

Mountain Goat Competition with Big Horn Sheep

One highly contentious issue in the West is the theory of transplanted goat populations competing with native bighorn sheep. I’m biased in this discussion because I love goats, and I have thousands of hours of time spent observing both species. I just don’t see how there could be a considerable conflict.

Most researchers observe limited overlap in habitat used. Estimates of 10% are common. If you look at broad swaths of mountain ranges, goats will overlap with sheep. However, the actual habitat they bed, feed, and socialize in has little overlap. Goats prefer steeper terrain, topography that sheep blatantly avoid. I have encountered goats close to sheep on many occasions, but I’ve encountered them far from each other on 100x as many other occasions.

The other argument is that goats are more aggressive towards sheep than sheep are towards goats. I do grant that I have observed this. Like they do with each other, goats posture and threaten sheep with “hooking” gestures periodically when they get near each other on trails. However, most of the time they just ignore each other. I find it hard to believe that these limited cases have a negative impact on sheep populations. I yet to see a goat run a herd of sheep off or stab a ram to death.

I’ve read all the available research on this topic and none of it proves a causal relationship between goats in a mountain range and the decline of bighorn sheep. I suspect that sheep are doing poor relative to goats in these ranges because they are less equipped to deal with growing predator numbers.

Hunting Strategies

These mountain goat hunting strategies all have their own pros and cons, but the choice of which you implement is essentially decided when you choose the area you hunt. All of these strategies take a certain amount of physical preparation, rely on glassing, and some fundamentals of stalking mountain goats.

Goat Stalking Fundamentals:

- Even habituated goats won’t tolerate approaching disturbance from directly below. However, the amount a goat will tolerate from a bumbling idiot above them is the 8th wonder of the world. Goats are use to rockfall creating movement/noise and they are complacent in assuming their habitat protects them from attacks from above. Stalks need to be planned so hunters approach from the topography higher than their bed or feeding location.

- Goats are forgiving when it comes to seeing you, but not forgiving when they smell you. This is tricky in the alpine because winds swirl in basins and thermals shift winds quickly during long stalks. Stalks need to be planned to anticipate changes in wind. Hunters need to understand thermals and use them to their advantage.

- Goats won’t cover much distance during the average 2-4 hour stalk, but that distance may take you all day to cover or their new location could make the goat untouchable. The topography can be brutal. The best time to start a stalk is when a goat beds in the morning. Goats tend to bed for 2-3 hours at this time and feed close by when they get up. Having a spotter keep tabs on the goat during your stalk is the ideal setup.

These two goat hunting stories will give you a feel for the typical goat stalk:

Spot/Stalk Glassing from Valleys

Although typically vehicle based, these are some of the most physical goat hunts. Many of our Colorado Mountain Goat Hunts and BC Goat Hunts fall in this category. Valley bottoms are traversed via hiking, boats, or vehicles. The top of each chute and back of each basin is glassed meticulously for a billy.

These hunts are best done with a guide that can judge billies from a distance as you will only get one, highly-physical stalk per day. You don’t want to gain 2,000 ft in elevation over 4 hours in rough terrain, to realize you are chasing a dry nanny.

High Alpine Backpacking

High Alpine Backpacking

Some of our Colorado hunts and Northern BC hunts fall in this category. Hunts that involve being dropped off at a high alpine lake via airplane of pack string are the epitome of this hunt style. These can be the least physically demanding hunts if you are dropped off in a lake basin that holds goats. If trophy billies aren’t in that basin, these hunts can be the most physically and mentally challenging hunts in North America. Hunters need to be prepared to cover ground and camp with minimalist gear.

Glassing is a lot like the Valley hunts, but you are focusing on terrain that is 200-800 feet above you instead of 1,500-3,000 feet above.

Patterning

This type of hunt is tough to pull off and is usually reserved for situations where a hunter draws a tag, but is not in physical condition to attempt the other hunt types. Hunters and guides will lay in ambush at watering locations, bedding areas with significant dusting history, and/or mineral licks. Hunters need to be patient on these hunts and tend to not have as many options when it comes to the quality of goat they harvest.

Sign up to get our new posts as they are published!

Cliff I couldn’t agree with you more on this article. I know nothing about goats but have hunted & trapped in my home state of Michigan since I was very young. I believe a lot of research & experts (which I encountered in college); have never really studied or know animals like hunters & trappers do. Really like reading your expertise that comes from experience. Reading the material that you have presented on this website is awesome. Thanks for sharing & educating.

Thanks Lloyd! Really appreciate the feedback and glad you find the articles useful.

Thanks,

Cliff

Excellent article and very informative! I am a guide/outfitter in Northern BC with tons of experience with bear and moose but I am relatively new to goat hunting. We do the high alpine backpacking method and everything you said is spot on from what I experienced so far. I learned a lot of new things from your article that I will try out in 2020. Thanks for sharing this information!